5

Learning Objectives

- Describe how agricultural originated and diffused

- Identify the various types of rural development patterns

- Compare the major forms of subsistence and commercial agriculture

- Discuss the key innovations in agriculture

- Analyze the impacts of modern agriculture

Think about what you eat on a given day. Does it look much like a plant or animal? Do you generally eat the same things for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, or do you have a wide variety of dishes that you consume in a given week? Does what you eat connect with your own cultural, ethnic, and/or religious heritage? How did you acquire the food you eat? Did you shop at a supermarket, drive through a local restaurant, or make it yourself? And who grew the food you’re eating and where was it produced? Perhaps it was grown in your own backyard garden! In many developed countries, we’re often quite removed from where our food comes from and we don’t often stop and think about how it gets on our plates. Much of our food doesn’t even look like a plant or an animal, and this makes it even harder to discern what we’re actually eating. Furthermore, what we eat has changed considerably over the span of human history, and continues to change as we look to the future. In this chapter, we’re exploring agriculture, the various food systems of the world and how food is grown.

5.1 Origins and Diffusion of Agriculture

Before we dive into our modern food system, let’s go back in time. How did agriculture begin? “Cultivate” actually means “to care for” and this is the root of the term “agriculture.” Agriculture refers to the science, art, and practice of cultivating plants and livestock. So what was life like for us before we began deliberately cultivating plants and raising livestock? Until around 12,000 years ago, we were all hunters and gatherers. Hunters and gatherers lived in small groups – generally less than 50 people. Why? Because if they lived in larger groups, they would quickly consume all food within walking distance. We hunted for animals, fished, and gathered a variety of plants like berries, nuts, fruits, and roots. Our search for food could take a short time, or much of the day, depending on environmental conditions.

It’s generally assumed that men were primarily hunters and women were primarily gatherers, but research actually shows that gender roles in ancient societies were not strictly defined. Furthermore, the ecological knowledge of plants and the nutrients they provided were critically important to hunter-gatherer diets and gave women an important role in ancient societies.

Hunter-gatherer societies were fairly isolated from one another. Groups might intermarry, or have disputes over hunting zones, but in general the large tracts of land required to sustain bands of hunter-gatherers meant there was relatively little interaction between groups and violent conflicts over territory were rare since groups could simply shift their territory as needed. For 90 percent of human history, this was how we obtained our food, and a few hunter-gatherer societies still exist in the world today, though their numbers have declined dramatically. Some members of the Hazda groups of eastern Africa, for example, still practice hunting and gathering (see Figure 5.1).

So how did we shift from hunting and gathering to staying in one place and growing the plants and animals ourselves? Agriculture developed independently in several different parts of the world and likely for a variety of different reasons. As some groups gathered food, they likely dropped a few nuts or berries along the way. They might have observed that, over time, these sprouted new growth. They might learn to add more water, or to help create more fertile soil, and you can see how this process could have evolved over time. Other groups might have been more intentional, perhaps driven by population pressures or climate changes, and may have thought, “I wonder what would happen if I stuck this seed in the ground…” Similarly, the domestication of animals likely occurred for a variety of reasons. For instance, people might have kept livestock for religious sacrifice. Or, we might have kept pets who ate our food scraps. From these hearth areas, agricultural practices later spread. These innovations are referred to as the Agricultural Revolution.

How did plants and animals actually become domesticated, shifting from the wild varieties we once found to the varieties we’re more commonly familiar with in the world today? We selected the seeds from the plants that grew the best, perhaps were the hardiest or produced the most yield. We also bred the animals that were the most docile or maybe the easiest to train. Think about cows today. Have you ever noticed they’re pretty laid-back? This is because, for generations, we first kept close to us and then bred those cows who were calm and docile. We did the same with dogs and cats.

There are two types of cultivation, vegetative planting and seed agriculture, and you might have tried these out in your own backyard or balcony gardens. Seed agriculture refers to the reproduction of plants by using seeds. Many plants like tomatoes and apples can be reproduced by planting the seeds that are found in the fruits. Vegetative planting, on the other hand, reproduces plants by using a fragment of the parent plant. Potatoes, for example, are grown using vegetative planting. You could cut up a potato, ensuring that each piece has an “eye” where a new stem could grow, and plant the pieces. New potato plants would sprout from each piece you planted. (Pretty neat, really.) The advantage of vegetative planting is that the new plants are essentially clones of the original plant. So, if you had a really tasty batch of potatoes, the new ones you planted would be genetically the same and should also taste great. With seed agriculture, seeds are generated through sexual fertilization and you control the parents of the plant, so it’s more like breeding in that you can introduce favorable traits. Maybe you have one variety of tomato that grows really well, and another that’s really sweet. You could cross pollinate the plants and viola – you’ve created a new tasty and hardy variety.

There are a number of hearth areas for vegetative planting and seed agriculture. Southeast Asia is a likely location for one of the first instances of vegetative planting. We see a lot of tree and root crops here, like taro, yam, and bananas, that would be suitable for vegetative planting. Additionally, the dog, pig, and chicken, were all likely domesticated in this region, as well. We also might have had a vegetative planting hearth in West Africa, around Ghana and the Cote D’Ivoire, with the planting of palm trees and yams. In South America, we see evidence of the cultivation of sweet potato, among other crops.

The location of seed hearths is a bit different, likely due to the natural environmental conditions and resources found in these locations. There are three main hearths in the Eastern Hemisphere: Western India, where crops like wheat were cultivated; China, where rice was first domesticated; and Ethiopia, where millet, sorghum, and teff, a cereal crop, were grown. As seed cultivation diffused to Southwest Asia, we saw the first domestication of herd animals, like cattle, sheep, and goats. Often, animals were used to plow the land, which was then used for planting, and part of the harvest was used as animal feed. We see two main areas of seed innovation in the Western Hemisphere, Mexico and Peru, each of which occurred independently. In Southern Mexico, we see the origin of squash and maize. In Peru, we find evidence of the domestication of cotton, squash, and beans.

Thus, beginning around 12,000 years ago, we began to shift from first planting wild varieties of crops we harvested to gradually domesticating and cultivating these plants and animals. This shift from hunting and gathering to more settled agriculture had a profound shift on how we lived. We no longer had to be relatively nomadic and could begin staying in one place for long periods of time. We could also support larger populations since we had a more reliable, and regular, source of nutrients. Put simply, our modern society today would not exist were it not for the development of agriculture.

5.2 Rural Development Patterns

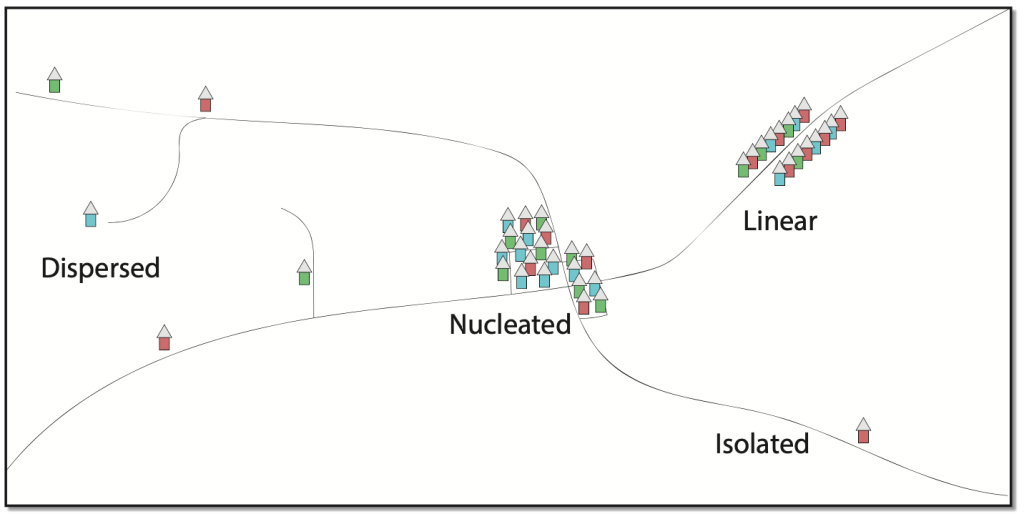

The practice of agriculture has continued to shape our land use patterns. Generally, farming takes place in rural areas. Rural settlements could be clustered (also called nucleated), where a cluster of homes are surrounded by fields, or dispersed, a form of settlement often found in North America where rural homes and farms are spread out and relatively isolated from one another; or linear, often arranged along a body of water (see Figure 5.2). Similarly, how rural land is divided is highly dependent on local geography. A long lot system is often used with linear settlements in order to give everyone access to a resource such as a river. The land is divided into long, narrow lots. French settlers established such a system in many areas they colonized, and thus remnants of the long lots system can be found in many parts of Canada and Louisiana. In other areas, rural land was divided into metes and bounds. Metes refer to specific distances between two points as well as an orientation and direction while bounds are more general, referring to local landmarks or physical geographic features. Metes and bounds was often used in England, and in areas colonized by the United Kingdom, and a parcel divided using a metes and bounds system might be described as “From the corner of the creek and the stone bridge, 200 rods (an old English unit of measurement) to the northwest to the large boulder…” and so on.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this relatively inexact form of parceling land has been replaced in most locales, but some areas continue to use this surveying system. The United States primarily uses the Public Land Survey System, which uses base lines and principal meridians to survey an area. A section of land is divided into townships, squares that are 36 square miles each north and south of the baseline. Ranges are used to measure the distance east or west of the principal meridian in units of 6 miles. A location surveyed with the township and range system might be described as “township 16 north, range 12 east.”

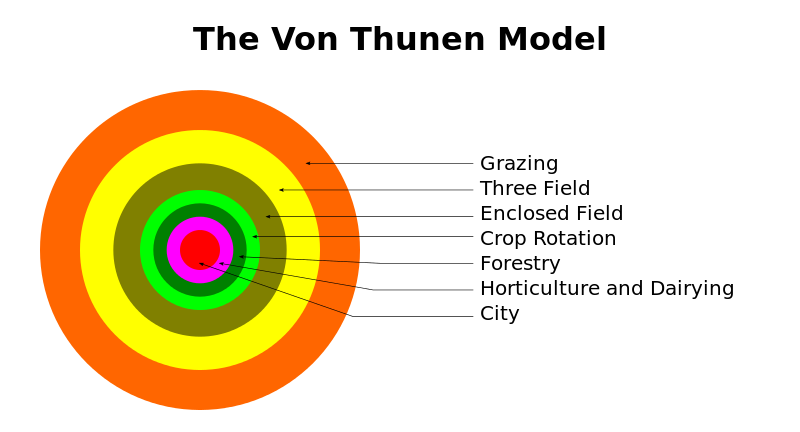

Historically, the actual crops grown on farmlands were directly related to the distance from the city center and the cost of land. Foods that spoiled quickly, for example, needed to be located near an urban center while crops that could store well and travel longer distances could occupy large tracts of farmland farther away where land was less expensive. The Von Thünen Model, first created by economist Johann Heinrich von Thünen in the early 1800s, describes the locations where these various agricultural products were produced in relation to the distance from the city center (see Figure 5.3). Dairying and horticultural production (including more perishable fruits and vegetables) were produced relatively close to the city, while fenced-in crops (“enclosed field”), three-field systems (where a crop like wheat or rye is planted in one field, another field has peas or lentils, and another field is left fallow), and grazing animals could all occupy land farther away.

While modern transportation, food processing, and refrigeration technology might have altered the neat rings of the original model, we still find this general model applicable on a broader scale. Globally, perishable products are still often produced close to the city center. Dairy farms, for example, still tend to be located near big cities in close proximity to bottling and processing plants for milk. Wheat farms are still located fairly long distances from major U.S. cities where land is more affordable – though bread factories are located near the cities themselves. Similarly, export crops are often those that travel long distances the easiest and are produced in less developed countries and shipped to more developed countries.

5.3 Forms of Agriculture

Given the wide variety of environmental conditions and native plants and animals found in the world today, it should be no surprise that there’s a wide variety of ways agriculture is practiced as well. If I were to ask you, “Where was the food you had for lunch grown?” you might answer a bit hesitantly, “On a farm….?” But what kind of a farm? And what happened to it after it was harvested? We’ve come a long way from our early days of growing crops and now relatively few of us are actually farmers, so many people know very little about how food is grown and produced.

One basic distinction can be made between subsistence agriculture and commercial agriculture. Subsistence agriculture is the growing of crops in order to subsist, meaning the crops are used to feed the farmer and the farmer’s family with relatively little left over for sale or trade. Commercial agriculture, on the other hand, is the growing of crops primarily for sale off the farm.

How can you differentiate between these two forms? There are a few guiding questions you could use to help distinguish between subsistence and commercial agriculture. First, what is the purpose of farming? Are you producing food for your own consumption or food for others? In commercial agriculture, it’s rarely sold directly to the consumer, but rather to food-processing companies. What percentage of the labor force is comprised of farmers? In countries where commercial agriculture is practiced, a relatively small number of farmers are able to produce large quantities of food. In subsistence agricultural areas, on the other hand, a high percentage of people are farmers. What machinery is used to grow and harvest the crops? In subsistence agriculture, farmers generally use hand tools and animal power. With commercial agriculture, the emphasis on high yields applies to the mechanisms used to farm as well and very often automated equipment – like tractors, pickers, etc. – are utilized. What is the size of the farm? Again, subsistence farmers are primarily producing food for themselves, so there is no need for sprawling plantations. Within the United States, the number of farms has decreased over time while the acreage of these farms have grown and this is common where commercial agriculture is practiced. Finally, what is the relationship of farming to other businesses? With commercial farming, food production is closely tied to agribusiness since a farm’s crops are not often sold directly to consumers.

Within subsistence and commercial agriculture, the actual practice of farming can take on many different forms and you might find several different types of agriculture practiced in the same country. There are four main types of agriculture practiced in less developed countries: pastoral nomadism, shifting cultivation, and intensive subsistence agriculture, which are all forms of subsistence agriculture, and plantation farming, which is a form of commercial agriculture.

Nomadic pastoralism is the herding of domesticated animals in search of fresh pastures for the animals to graze. Contrary to what you might think, herd animals are generally not slaughtered, but are instead more commonly used for their milk. Once dead, their skins and hair can be used for clothing and tents. Animals might be chosen based on its environmental adaptations, like the camel, or on the prestige of an animal. Other herded livestock include cows, goats, llamas, and even reindeer. Also note that while these groups are nomadic, they are not random wanderers. Rather, they follow migration patterns that have developed over thousands of years.

Today, there are between 30 and 40 million nomadic pastoralists, but there used to be far more. Why is that? Well, consider how much land is required for nomadic pastoralism. Furthermore, consider how the modern political geographic landscape has made nomadic pastoralism challenging with international borders and the divvying of land into privately owned parcels. Nomadic pastoralism is often practiced in less fertile environments where other forms of agriculture may be limited. The Raika people of the state of Rajasthan, India (see Figure 5.4) are semi-nomadic and have been herding camels for hundreds of years, but now, as with many nomadic pastoralists, their way of life is under threat. They no longer have access to the lands they’ve traditionally used for grazing and fences often block their paths.

Shifting cultivation is a form of subsistence agriculture where people shift (hence the name) cultivating one plot of land temporarily and move to another piece of land for a period of time. Each field is used for crops for a few years and then left fallow for a relatively long period. Eventually, farmers return to the plot of land, which is now overgrown with vegetation. Some farmers who practice shifting cultivation then cut and burn the vegetation (known as slash and burn) in order to create a cleared patch of fertile soil known as swidden (see Figure 5.5). This burning of vegetation actually infuses nutrients into the soil. Other farmers simply clear the vegetation by cutting.

With shifting cultivation, a patch of land is generally only used for 2 to 3 years and then left fallow for anywhere from 6 to 20 years. While shifting cultivation can look quite destructive, as it has historically been practiced, it is actually more ecologically sustainable than it might appear. Soils can only support crops for so long before they run out of nutrients. With commercial forms of agriculture, fertilizers are often used to infuse more nutrients into the soil. With shifting cultivation, the land needs no external inputs and is left to recover naturally on its own. One challenge to shifting cultivation, though, is that it is more ecologically sensitive when it is practiced on a small scale. Larger groups need to burn larger tracts of land, which could be more detrimental to the environment. Another challenge is the sheer amount of land needed to support shifting cultivation. With this form of agriculture, you need three to four times the amount of land as you would with commercial farming, since each plot of land is only cultivated for a short period of time. While this might not have been a challenge for early humans, who had relatively small populations and large areas of land to roam, it is much more challenging in today’s society. It has also made groups practicing shifting cultivation more vulnerable to takeover or to the parceling of their land, since land that may look unused may actually be lying fallow. Around 250 million people practice shifting cultivation today.

As areas grew and developed, less and less land was available for farming and farmers who once had large areas of land to cultivate and harvest were left with smaller and more challenging tracts. Often this led to more intensive subsistence agriculture. Intensive subsistence agriculture is a form of subsistence agriculture where farmers cultivate a small area of land using additional effort. This form of agriculture is often found in areas where agricultural density, the ratio of farmers to arable land, is quite high. Because the density is so high, farmers have to be able to produce a tremendous amount of food from a very small parcel of land. And as mentioned, this land may be less desirable if an area has limited land available and a high population. So, how do you grow crops like rice, which must be grown on flat land, on the side of a steep hill? You could build terraces, essentially creating flat “stairs” along the side of the mountain that are suitable for growing crops (see Figure 5.6).

Plantation agriculture, where large farms specialize in the production of one or two crops, is found in less developed regions. Why is that? When areas were colonized, the focus was generally on exporting resources. A plantation is essentially a very efficient way to produce large amounts of food for export. But why would they only grow one or two crops? Imagine you’re playing a farming video game and you’re trying to earn a lot of coins (or bells or cash, etc.) How would you arrange your farm? If you have a piece of land and a variety of crops, they might have different growing patterns and watering needs. Some might be able to be harvested daily while others could take a week to be ready. If you wanted to maximize your profits, and minimize the time spent playing the game (because you might have other things to do), you could just plant one type of crop. That way, they would all need the same amount of water, grow at the same rate, and harvest at the same time. Plantation style agriculture follows the same essential principle – minimizing time and cost while maximizing efficiency and profit by growing just one or two crops. Plantations are usually located in sparsely populated areas since they utilize large areas of land, so owners must import workers or laborers. In the Americas, slave labor was generally used on plantations. While the use of plantations in the United States declined after slavery was abolished, “monocultures” are now the norm – and a monoculture, where a single crop is cultivated, is essentially a modern version of a plantation. Even in areas that are no longer colonies, plantation agriculture is still commonly practiced with crops sold and exported to more developed areas. Chiquita Brands International, for example, an American company which was called the United Fruit Company until 1984, owns a tremendous amount of land in Central America operating sprawling plantations that produce fruits like bananas for export (see Figure 5.7).

In more developed countries, we find several forms of commercial agriculture including mixed farming, where crops are cultivated alongside the rearing of livestock and crop rotation is often practiced; specialized horticulture, to include the cultivation of fruits and nuts; commercial grain farming, where grains like wheat are grown primarily for human consumption; dairy farming; and livestock ranching. Where these types of farms are found is highly dependent upon local geography and resources. Grain farming, for example, is found extensively across the central United States, where ample tracts of large, flat land and seasonal rains support crop growth. Livestock ranching is found in regions that might not have enough fertile soil or irrigation to support other forms of agriculture, such as in Australia’s Northern Territory.

More broadly, we can characterize a number of forms of commercial farming as industrial farming, meaning that food is not only produced primarily for sale off the farm, but is also produced using a highly mechanized process. One commercial farm might grow a variety of crops alongside several species of livestock who are allowed to graze and these products are sold at local farmer’s markets and to restaurants. Another commercial farm might produce only chickens in sprawling chicken houses where flocks of tens of thousands per house spend their entire lives indoors.

5.4 Agricultural Innovations

We’ve come a long way from our early days as farmers – so long in fact that most people in more developed countries no longer need to grow food and a relatively small amount of farmers are able to feed a considerable amount of people. How is this possible? The Second Agricultural Revolution accompanied the Industrial Revolution and allowed farmers to harness new technological innovations to increase productivity. Some of these innovations related to mechanization, helping farmers to produce and harvest more food with fewer people, but others were more related to the science of farming. Crop rotation, for example, was one of the most important innovations during this time. By rotating crops, farmers could restore nutrients in the soil and improve its fertility. One four crop rotation in particular – wheat, turnips, barley, and clover – came to dominate during this time period as it eliminated the need to keep a field fallow and allowed year-round grazing of livestock. The selective breeding of livestock was another innovation during this time period, and cattle began to be bred specifically for beef (whereas previously farmers primarily kept cows for dairy uses.) New fertilizers were also discovered and came into wide usage, again increasing plant yields. While this period of change is often termed the “Second Agricultural Revolution,” it was really more of an extended process of a series of broad changes rather than a short-termed period of intense innovation.

These innovations coincided with the Industrial Revolution but also helped fuel and sustain it. Fewer farmers were needed at the same time increasing numbers of industrial jobs were developing in urban areas. Without the surplus of food created through the Second Agricultural Revolution, there would not have been the large urban populations that developed during the Industrial Revolution. Around this same time, food processing techniques developed and mechanized as well, such as the canning of food on an industrial scale.

The next major revolution in agriculture came in the 1950s and 1960s. This is known as the Green Revolution and refers to the innovations that resulted from the use of new technologies that significantly increased global agricultural production. As with the Second Agricultural Revolution, the Green Revolution is more than just a single innovation or new technique. Rather, the Green Revolution had a number of significant technological innovations aimed to increase yield. One key innovation was the development of high yield varieties of wheat, creating new hybrid varieties capable of absorbing more fertilizer. Fertilizers themselves changed dramatically during this time with the creation of chemical fertilizers, such as nitrogen fertilizer which is derived primarily from natural gas. Irrigation systems and the use of pesticides also served to increase crop yields during this time.

The increases in production that resulted from the Green Revolution are credited with increasing the global food supply and potentially averting famine. The innovations of the Green Revolution led to other challenges, however. One is that the increase in mechanization and chemicals marked by the Green Revolution made farming considerably more expensive. Smaller farmers often went into debt and farms began to consolidate and get larger. In addition, while the Green Revolution allowed land to be more fertile, this increase fertility was only achieved through chemical fertilizers, which are energy-intensive to produce and environmentally detrimental. It also encouraged the expansion of farmland in areas which were previously unproductive – a benefit to farmers who might not have otherwise been able to grow crops, but a potential threat to local biodiversity as land was cleared to create farms. The hybrid varieties of seeds, while high yielding, were sometimes less nutritious than more traditional varieties.

5.5 Modern Global Agriculture

The way we farm today in both less developed and more developed countries is a direct result of the Green Revolution. The practice of applying scientific innovations and mechanization to the cultivation of plants and animals is characteristic of the modern way we produce food. Even our meat production has become highly mechanized, with most meat worldwide coming from livestock reared on concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) (see Figure 5.8). While these types of concentrated feedlots seek to maximize profits by creating a highly efficient production process, having animals so tightly concentrated has significant environmental impacts, from the fuel and water used to bring in animal feed to the large amounts of waste produced to the increased spread of disease due to living together in such close quarters.

The development of hybridized seeds during the Green Revolution has continued, with further innovations in genetic modification allowing scientists to tweak the DNA of plants, making them less susceptible to diseases, more resistant to spoilage, and more resistant to chemical herbicides. This increased use of genetically modified crops (also known as GMOs for genetically modified organisms) have come to dominate modern farming and have led to substantially higher crop yields. As with some of the innovations during the Green Revolution, however, these higher yields have come at a cost, both in terms of the high costs of the GMO seeds themselves which are patented, but also the environmental impact of using additional fertilizers and pesticides.

These changes, particularly the industrialization of agriculture, have also reduced the varieties of crops that are grown. For example, there are over 1,000 different varieties of bananas in the world today, but most of us eat only one. The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita), for example, began growing a single variety of banana in all of its farms in order to simplify and standardize production. These bananas were genetically identical, reproduced through vegetative planting, which ensured that it was exactly the same regardless of the locale. A disease began to wipe out the banana crop in the late 1800s, and so United Fruit Company turned to another variety, the Cavendish banana, which is the essentially the only variety found in stores in Europe and North America today. Unfortunately, the disease that wiped out the previous banana crop has evolved to be deadly to the Cavendish variety as well and is expected to similarly wipe out the entire species in the future. This is the risk of relying on a single variety of crop, essentially putting all your eggs (or bananas, in this case) in one basket.

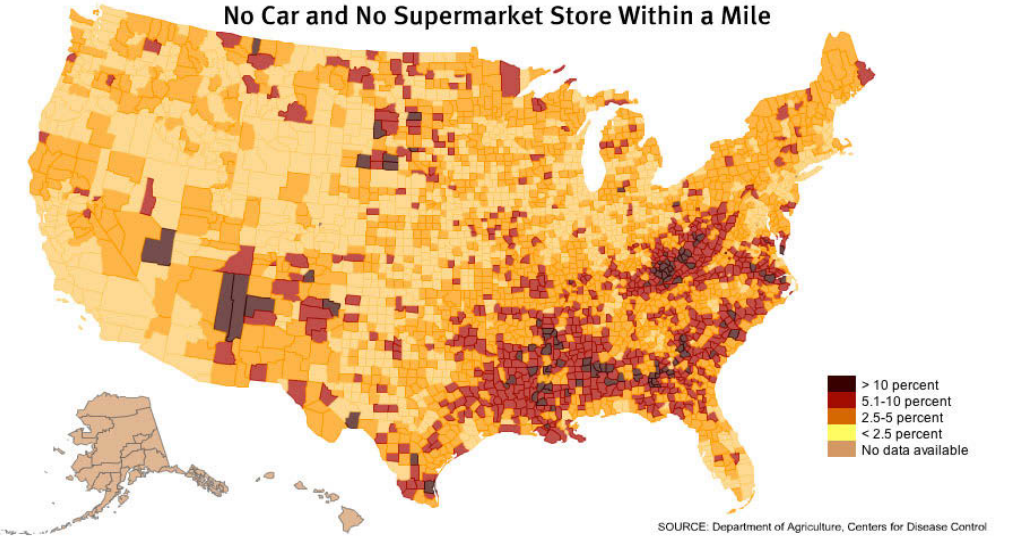

In addition, despite the Green Revolution’s impact on increasing the global food supply, we continue to have issues with malnutrition across the globe. Malnourishment broadly refers to a diet that does not supply a healthy amount of nutrients. Many often think of undernourishment when they consider malnourishment, which is when someone does not consume enough calories, protein, or specific nutrients, and certainly undernourishment is a very real concern for many people in the world. Globally, over 10% of the population, or around 821 million people, are considered undernourished. In the United States alone, 35.2 million people lived in food-insecure households in 2019 according to the USDA. Overnutrition is also a concern, however. Around 13% of adults in the world are obese, and one in five children and adolescents are considered overweight. Obesity was linked to 4.7 million deaths worldwide in 2017 and rates have increased in recent decades. In many cases, poverty is at the root of malnutrition in all of its forms. We find the highest rates of undernourishment and the highest obesity rates in low and middle income countries as well as in poorer communities within high income countries. Put simply, poverty limits a person’s ability to access a an adequate supply of healthy foods. Even within the United States, many low income areas are considered to be food deserts (see Figure 5.9), where residents have limited access to affordable, nutritious foods, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables.

Modern global agriculture is broadly characterized by consolidation. Certainly the growing of foods has been consolidated, shifting from many smaller farms to a few very large farms. The grocery store industry, too, has consolidated, with the number of individual stores declining and companies often merging or acquiring smaller stores. Even the very foods we eat have also consolidated, though it’s not often apparent from the rows and rows of seemingly endless varieties of foods in the modern supermarket. In reality, the vast majority of the processed food we eat is derived from a very small number of crops. Corn, for example, is in almost every product in a supermarket. High fructose corn syrup sweetens everything from ketchup to soda to processed breads. Maltodextrin, a food thickener often created from corn, is used in infant formula and some snacks. And the list of corn-derived products goes on. Soy, too, has come to dominate much of our diet, with soy additives in a variety of processed food products.

The production of these foods has also consolidated. As mentioned, commercial agriculture is marked by the production of food primarily for sale off the farm. Increasingly, these foods are not sold directly to the consumer but rather to an intermediary company. Agribusinesses refer to companies connected with the production of food. It is a combination of the terms “agriculture” and “business,” so these are essentially businesses related to agricultural production. Companies that produce farm machinery are considered agribusinesses, as are seed and chemical manufacturers and food processing companies. These large, multinational corporations dominate the various sectors where they operate. Four large companies control 75-90% of the global grain trade, for example. Six companies control 75% of the agrochemical market. And similarly food processing companies have often merged or bought smaller companies. Have you eaten a PepsiCo product lately? It’s one of the largest food, snack, and beverage companies in the world, second only to Nestlé, and even if you don’t drink Pepsi soft drinks, you might not have realized you were eating a product they manufactured. They own everything from Quaker Oats to Gatorade to Tropicana. So walking through the grocery store, what seems like an endless array of products and companies and varieties is really a relatively small number of crops and their derivatives processed by a handful of large companies.

So what is the modern human to do? Curl up and cry with a bag of Cheetos? (Which is owned by Frito-Lay, a subsidiary of PepsiCo.) It can be difficult to know how to make the right food choices, both for ourselves and the environment, in such a complex, and often obscured, system. There are a number of sustainable solutions to our various agricultural challenges. One set of solutions relates to the practice of farming itself. Sustainable agriculture refers to farming in ways that are able to meet the needs of people today without compromising future generations. There are a wide array of sustainable farming practices, from soil management techniques like no-till farming (which helps prevent erosion and retains soil moisture) to practicing crop rotation to planting cover crops. Many of these practices are reminiscent of our early ways we farmed, considering the larger ecosystem rather than just a single crop.

Many women worldwide work in agriculture, including a majority of women who are economically active in less developed countries and around 43 percent of the agricultural labor force in developing countries. However, gender inequality in agriculture persists, particularly with regards to access to resources like land, financial services, and education. In fact, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations estimates that if women had access to the same resources as men, it would ultimately reduce the number of hungry people in the world by 100 to 150 million. Women have also increasingly turned to sustainable farming techniques and a number of global partnership programs have been created to both increase access to resources for women farmers and encourage sustainable agricultural practices.

Consumers, too, can help shape a more sustainable agricultural system. Across the United States, the number of farmers markets has increased, providing a direct link between consumers and those who grow their food. And farmers markets are not just for the wealthy – in fact, contrary to what you might expect, farmers market prices are generally competitive with regular supermarket prices and many local markets accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (previously known as “food stamps.”) Consumers can also be mindful of food waste. Astoundingly, around 1/3 of all food produced worldwide is never eaten. There are a variety of reasons why so much food is wasted, including farmers discarding imperfect foods (that would have tasted fine but did not meet the visual standards of consumers in more developed countries), uneaten foods that are discarded at home, and foods that are discarded close to their “best buy” (even though this is a voluntary system of labeling that reflects only the quality of the food, as determined by the manufacturer, and not safety.) Many non-perishable foods are still perfectly fine even a year or more past the “best buy” date and there are numerous guides online to help consumers know how long these dates can be extended. The very foods we choose to buy sends a message to food producers and manufacturers about what we value. So, when we buy something from a small company that practices sustainable agriculture or shop locally or buy organic, we are essentially voting with our dollar and shaping the future of agriculture.

the science, art, and practice of cultivating plants and livestock

the transition from hunting and gathering to the domestication of plants and animals

the reproduction of plants through the use of seeds

the reproduction of plants using a fragment of the parent plant

long, narrow divisions of land usually lined up along a waterway

a boundary defined by a specific distance between two points as well as an orientation and direction

general boundary descriptions that utilize local landmarks or physical geographic features

a form of agriculture where a farmer grows crops primarily to feed themselves and their families

a form of agriculture where crops are grown primarily for sale off the farm

a form of subsistence agriculture where domesticated animals are herded in search of fresh pastures for the animals to graze (also known as pastoral nomadism)

a form of subsistence agriculture where farmers cultivate a small area of land using additional effort

a form of commercial agriculture where large farms specialize in the production of one or two crops

a form of farming where a single crop is grown

the increases in agricultural production that coincided with the innovations created during the Industrial Revolution

agricultural innovations that resulted from the use of new technologies in the 1950s and 1960s that significantly increased global agricultural production

a company connected with the production of food